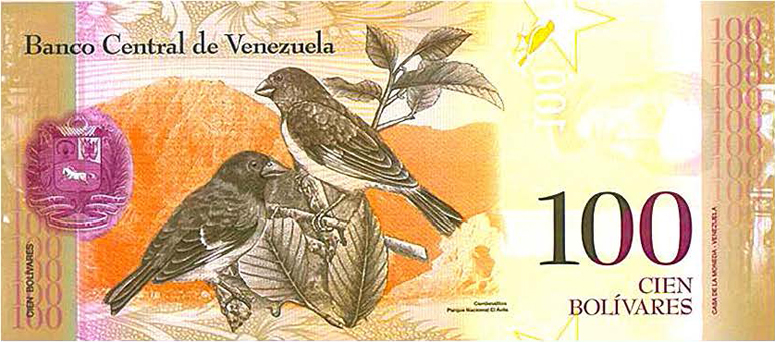

In Venezuela, the red siskin (Sporagra cucullata) is known as el Cardenalito—or “little cardinal”—a tribute to its vibrant colors. This charismatic bird is part of the country’s national identity: It is the official bird of Lara state, the subject of well-known folk songs, and its image appears on the highest denomination currency, the hundred bolívar fuerte note. It is also one of the most endangered birds in the world.

The red siskins’ distinctive red-and-black plumage made it desirable. The feathers and even whole birds adorned elaborate women’s hats and other clothing items in the early 1900s, and it has been a popular caged bird in many countries. Great numbers were captured for the pet trade, and even now trapping continues illegally. But the main reason for its disastrous decline was the popular early 20th-century quest to produce a red canary, causing the red siskin to be trapped almost to extinction to meet the demand of aviculturists who were hybridizing it with domestic canaries.

The red siskin once graced the skies in large flocks across northern Venezuela into Colombia and the island of Trinidad. Now the bird has disappeared in many of these places, and the few isolated groups in Venezuela may number only several hundred individuals. In recent decades, sightings in the wild have been increasingly scarce. That is, until a Smithsonian/University of Kansas expedition traveled to the Rupununi savannas of southern Guyana in 2000 and discovered a previously undocumented population.

That expedition was co-led by Michael Braun, a research scientist in the Department of Vertebrate Zoology at the National Museum of Natural History, and Mark Robbins, collections manager for ornithology at University of Kansas, who first spotted the rare birds. “It was like seeing a ghost,” says Braun. “Ornithologists had pretty much given up on this bird in the wild, outside of a small, local population in far western Venezuela near the border with Colombia.”

Robbins, recollecting the moment of discovery in Guyana said, “Quite unexpectedly, I heard siskins calling as they flew overhead and out of sight. A few minutes later I found the birds, including a male, sitting in the top of trees. When I realized what they were, I thought I must be dreaming.”

Even in their excitement, the researchers realized how extremely valuable these birds would be on the international black market for the pet trade, so they kept the information about their find a close secret while they sought official protection for the red siskin in Guyana. After it was added to the country’s endangered species list and legal protections against trafficking were in place, the scientists were able to publish their findings—without specific location information—to announce the discovery of Guyana’s population of red siskins to the ornithological community.

This important discovery attracted the interest of conservationists in Venezuela, who contacted Braun about protecting this bird. And from this, the Red Siskin Initiative was born.

The Red Siskin Initiative

Saving the red siskin has become a passion for Braun. He came to the Smithsonian 27 years ago to start a molecular genetics laboratory for the Institution, but also because he has always been interested in the biodiversity of the tropics. For his entire career, he has been involved with museum collecting and biodiversity documentation. Now, in addition to his work in genetics, he spearheads the Red Siskin Initiative, a multifaceted conservation effort to bring the bird back from the brink of extinction.

The Red Siskin Initiative is an international partnership of public and private institutions that aims to protect the population in Guyana and restore sustainable populations in Venezuela through reintroduction. The Smithsonian’s participation is significant, hosting the project coordinator position and drawing on expertise from Smithsonian scientists at the National Zoo, Conservation Biology Institute, Migratory Bird Center, Tropical Research Institute and National Museum of Natural History.

Project coordinator Brian Coyle explains: “It’s such a comprehensive effort—it includes habitat protection, captive breeding, sustainable agroforestry, education and community involvement, plus a cutting-edge genomics aspect that’s really exciting. It can serve as a model project for modern conservation.”

Guided by Genomics

In many ways, genomics will guide conservation efforts. Because extensive breeding efforts with other species like canaries have created numerous hybrid birds, it is important to be able to identify birds that look like red siskins, but have mixed ancestry, and exclude them from captive breeding programs for reintroduction. Critically small populations are also prone to inbreeding, with the associated health concerns. Genetic methods can gauge relatedness among potential mates to prevent inbreeding and insure success of breeding efforts.

The first step is to assemble a whole genome for the red siskin. By combining short-read and long-read DNA sequence data, a novel hybrid-assembly approach developed by scientists at the University of Maryland, they expect to produce one of the highest quality genome assemblies of any bird.

Armed with the red siskin’s whole genome, plus low-coverage shotgun sequencing of nine other wild individuals from Venezuela and Guyana, researchers can develop molecular tools to identify hybrid birds, prevent inbreeding, find markers for genetic disorders or disease, and understand the genetic differences between the two populations. The latter has become immediately relevant; preliminary data indicates that the two populations are genetically diverged to an extent that they will probably need to be managed as separate populations, and not bred together, in order to maintain evolutionary distinctness of each population.

The project is also working with Jesus Maldonado at the Smithsonian’s Conservation Biology Institute to extract DNA from museum specimens collected in the 19th and early 20th centuries across Venezuela and the Caribbean. These samples are critically important to understanding past genetic diversity and population structuring that will help inform future conservation management.

Maldonado says, “Our group at SCBI has played a big role in the development of ‘ancient DNA’ technologies to extract, capture and sequence DNA from old museum specimens. DNA from these ancient specimens gives us a more complete picture of how the red siskin has changed genetically over space and time.”

Reintroduction in Venezuela

The Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute is an internationally renowned conservation breeding center with more than 3,000 acres of land in Front Royal, Virginia. At SCBI’s Center for Species Survival they breed many at-risk species, like cheetahs, as well as endangered birds.

“SCBI has the facilities, expertise and veterinarians,” says Braun. “Brian did the legwork to find the birds and get the effort organized, and we now have a research colony of red siskins there. The role of SCBI will be to study this little-known species and carefully develop the animal management, breeding and reintroduction techniques that we can then translate into action in Venezuela.”

Warren Lynch, bird unit manager, is in charge of the red siskin colony at SCBI together with Paul Marinari, senior curator of animal operations. “This is a very rare bird that is also an important symbol for conservation in a biodiversity hotspot,” says Marinari. “By bringing together expertise from across the Smithsonian, we believe we have a good chance to add to the scientific knowledge of this bird in a highly visible way that inspires crucial support for more conservation efforts in the region, but also builds vital capacity for in situ and ex situ conservation approaches in a place where it can have a big impact.”

With this knowledge, SCBI will provide scientific support for conservation breeding programs at two Venezuelan zoos—Parque Zoológico y Botánico Bararida in Barquisimeto and Parque Zoológico El Pinar in Caracas—that are working on a program to breed large numbers of birds for reintroduction in the wild. Another participant, William Ruhl and his Boston-based firm, Ruhl Walker Architects, is designing an entire facility for red siskin breeding and education, providing these services pro bono.

Provita is the lead partner of the Red Siskin Initiative in Venezuela. The NGO, located in Caracas, has an impressive 25-year history of conservation of a number of diverse species, including the successful reintroduction of a parrot species on an island off the coast of Venezuela. Provita contributes to almost all facets of the Red Siskin Initiative and has a dedicated coordinator for the project. “For Provita, the Red Siskin Initiative is a priority project that represents a real opportunity for Venezuelans to rescue an iconic species from the brink of extinction, a symbol for the whole nation,” says Miguel Arvelo, project coordinator for Venezuela.

In the field, conservation scientists from the Smithsonian’s Conservation Biology Institute, Migratory Bird Center and National Museum of Natural History are working closely with the Venezuelan Institute for Scientific Research led by conservation biologist Kathryn Rodriguez-Clark to study population parameters, behaviors and habitat requirements to develop a habitat model to identify suitable areas for reintroduction. “Understanding the siskin is critical for establishing effective conservation actions,” says Jhonathan Miranda, who leads fieldwork for IVIC. Fortunately the red siskin can do well in human occupied areas, however it is still necessary to protect their natural habitat, which is threatened by urban development.

Release sites may eventually include coffee and possibly cacao farms that can meet the habitat requirements for red siskins and are certified as “Bird Friendly” by the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center. Bob Rice, Migratory Bird Center research scientist, says, “Coffee agroforestry systems have been shown to provide viable, quality habitat for migrant and resident birds alike. Reintroduction of red siskins into Venezuela’s shade coffee farms will create showcases for a threatened species and link conservation of this remarkable bird to the marketplace via a cup of coffee.”

The Red Siskin Initiative will work with community members and other stakeholders on public and private lands surrounding these farms to promote local stewardship of red siskins and develop a formal monitoring and reporting system to combat illegal trapping.

Protection in Guyana

Guyana’s red siskins are found in a remote area of about 70 by 100 miles. Since there seem to have been no known threats to this population prior to its discovery in 2000, monitoring and protection may be sufficient to sustain this population without additional external breeding efforts. However, habitat protection remains a priority, especially with the recent introduction of industrial mechanized agriculture to the area and the increasing frequency of fires in the savanna.

The main partner in Guyana is the South Rupununi Conservation Society. Many of the founding members of SRCS were guides and assistants to the Smithsonian expedition that discovered the red siskin population in 2000. “We have raised awareness of the bird in local communities, stopped its capture by local caged-bird traders, and guided many visiting birdwatchers to their first sightings of this exceedingly rare bird,” says Chung Liu of the SRCS. “Our experiences have been invaluable in understanding the feeding habits and behavioral patterns of this minute and rare bird.”

Researchers from the Smithsonian, SRCS and collaborating organizations have been conducting field studies to define the population size, density and distribution. SRCS has been collecting blood samples so that the Smithsonian can assess genetic diversity and viability, and they are also banding birds for future studies.

Recently, the project has been collaborating with the Environmental Protection Agency–Guyana and Bird Life International to develop strategies for red siskin habitat protection that include establishing an Important Biodiversity Area.

Reducing Threats and Promoting Community Pride

Another focus of the Red Siskin Initiative is reducing the demand for wild birds. Educational strategies, backed by science, are being used to help members of the international avicultural community connect their actions to the decline of threatened species. On an even broader scale, the project is engaged in research, education and collaboration with national and international organizations to address the threat of illegal wildlife trafficking.

Development of a formal system for monitoring and reporting illegal wildlife trapping and suspicious activity in the south Rupununi has been proposed by SRCS and Smithsonian, as well as training customs and enforcement officials in identification of threatened wildlife and developing a national campaign to broaden awareness and education about the value and vulnerability of Guyana’s famed biodiversity. Together with Rare, an NGO, they intend to hold a future Community for Conservation workshop that will train local participants in social marketing techniques to deter trapping and nurture a greater appreciation for natural heritage.

Influencing public attitudes through education, and instilling a sense of pride in species like the red siskin, can generate powerful support for conservation efforts. In Venezuela, zoos are working to rescue birds confiscated from illegal trafficking, leading community outreach efforts to find alternatives to illegal trade, helping to build national pride in the species, and educating the public about how to help protect these birds.

In Guyana, efforts are focused on nurturing a culture of community pride and support for protection of the red siskin through training in conservation research and administration for volunteers from communities in the Rupununi region, promoting sustainable economic opportunities like eco-tourism and shade coffee, and developing a variety of environmental education programs for Amerindian schools and villages.

A Teachable Moment

The red siskin is a high profile, charismatic, endangered species, and saving it will generate knowledge and awareness that can be translated to other threatened species.

“It's a teachable moment,” says Braun. “This bird is endangered because too many of them were harvested without regard to what the natural population could sustain. And that lesson then translates to many, many other aspects of how humans use and interact with their environment, such as overfishing, clear-cutting of forests and overdependence on fossil fuels.”

“We hope to have success at reintroducing the red siskin and recovering it to the point where it doesn’t need intensive management,” continues Braun. “It can be an example of wise use of the environment so that people understand that we need to pay attention to all aspects of how we’re using the environment in order to sustain the biodiversity and ecosystem services that we take for granted.”

For more information, go to RedSiskin.org.